My first one was a suicide.

A middle-aged man overdosed on pills in the front seat of his red pickup truck in a forested area about forty-five minutes outside of Corvallis, Oregon. He'd probably been dead, oh, maybe a day, twenty-four hours or so. He'd left a note on the front seat next to him. I drove the van with the mortuary science student who lived in an apartment connected to the embalming room at the back of the funeral home. The road was dark and winding, it was 2am and I was nervous. And twenty-three years old.

We met the police there, as the undertakers' assistants, like me, were the Girl Fridays of the local death scene. (I was, in fact, the only Girl Friday in town, and there were only a handful of Boy Fridays, I should note.) There was no morgue at the city hospital, so we did the dirty work for the police, doctors, and the like, picking up bodies from all sorts of locations and end of life scenarios, from automobiles in the mountains to attics of houses to nursing homes. We helped the coroner perform autopsies and embalmed and cleaned up messes and held people's hands.

Both dead and alive.

I decided I might want to become a mortician about a year before that, a young girl finding her calling. After having heart-to-heart conversations with funeral directors around Idaho and Oregon that I interviewed, they suggested I get a job in the field first before committing to mortuary science school (I already had two bachelors degrees at this point and getting a third was something I needed to think about) to see, you know, if I had the stomach and the heart for such a gut-wrenching career.

It was so hard, they said. I wouldn't recommend this field to anyone, they shared. It is a calling and a career that can keep you up all night and away from your family on birthdays, they lectured. Funeral directing will drive you to drink, they warned.

They hired me at one of two funeral homes in Corvallis to be a mortician's assistant/night-time removal driver. I had a pager and worked full time during the day, awaiting deaths in the dark of the night. And they came, sometimes more than one a night. And I took off my pajamas and brushed my teeth and threw on some nice conservative black clothing, drove to the mortuary, picked up the unmarked minivan and met the family/nurse/staff/police at a number of locations. Physically, dead weight is hard to carry. Emotionally, it's even harder.

I have stories to tell that will knock the wind out of you, make your stomach churn, make your heart break. People hugged me, screamed at me, said I was too young, too beautiful, too sweet to be doing this job.

You make me feel better, she said. Your kindness is so soothing, they told me. I'm floored that a young woman is here to take my father away but I'm so glad you are, I once heard. I hate you, she cried. Please don't take him away, they yelled down the hall, tearing at my clothes.

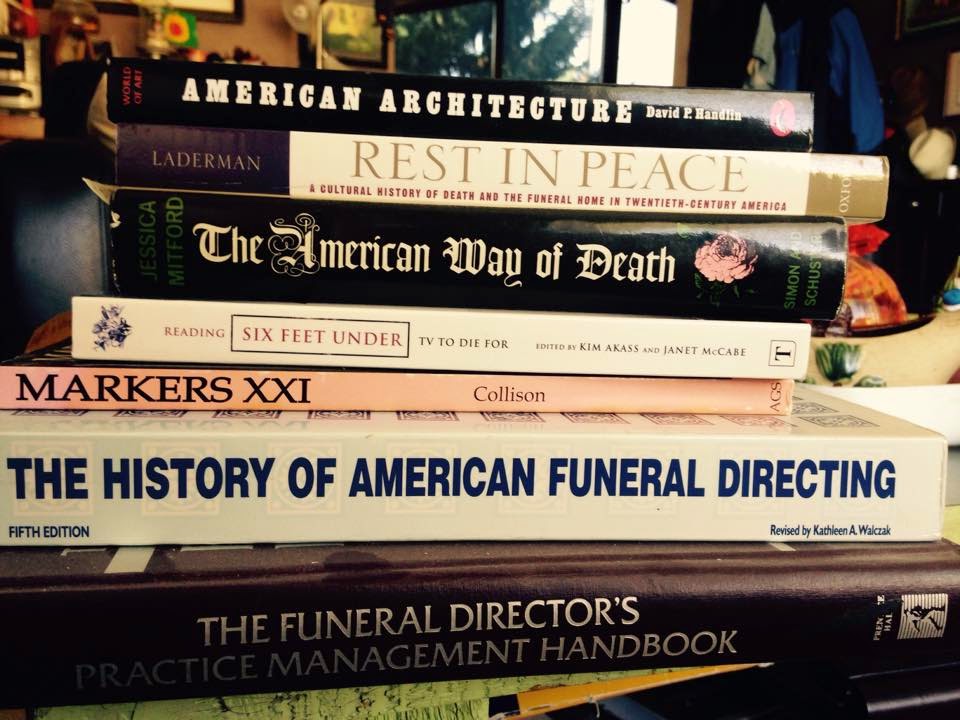

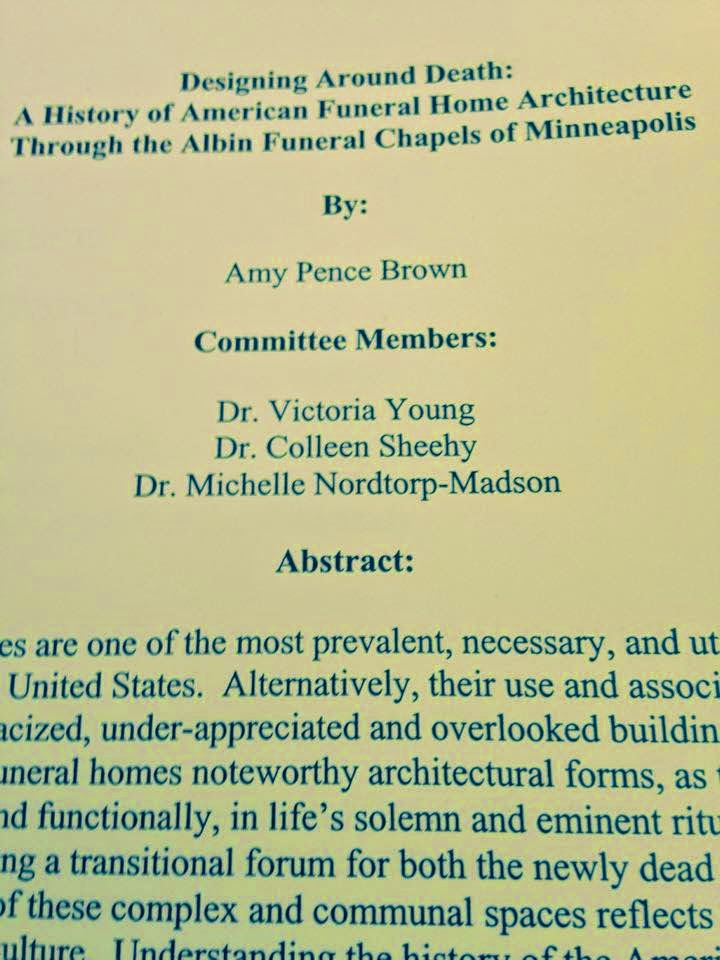

In graduate school I found myself studying art and architectural history, continuing to learn about the American way of death. These stories bore a hole in my heart and my mind and my academic research. It can be different. It should be different.

Fifteen years later this young, sweet, beautiful girl in California picked up where I left off, and I'm so glad she did. Her YouTube videos, Ask A Mortician, are charming, relevant and on the mark.

Caitlin Doughty is a mortician who's telling you that you don't really need a mortician to mourn and bury your loved ones. Home funerals and green burials and bringing death back to our conversations is such an important movement. She's also founder of The Order of The Good Death and writer of a new book and recently interviewed by Terry Gross on NPR. All of these things are so, so, so worthwhile, friends. Please give them a watch, read, glance. It's kind of a matter of life and death.

And fun! (For real.)

A middle-aged man overdosed on pills in the front seat of his red pickup truck in a forested area about forty-five minutes outside of Corvallis, Oregon. He'd probably been dead, oh, maybe a day, twenty-four hours or so. He'd left a note on the front seat next to him. I drove the van with the mortuary science student who lived in an apartment connected to the embalming room at the back of the funeral home. The road was dark and winding, it was 2am and I was nervous. And twenty-three years old.

We met the police there, as the undertakers' assistants, like me, were the Girl Fridays of the local death scene. (I was, in fact, the only Girl Friday in town, and there were only a handful of Boy Fridays, I should note.) There was no morgue at the city hospital, so we did the dirty work for the police, doctors, and the like, picking up bodies from all sorts of locations and end of life scenarios, from automobiles in the mountains to attics of houses to nursing homes. We helped the coroner perform autopsies and embalmed and cleaned up messes and held people's hands.

Both dead and alive.

I decided I might want to become a mortician about a year before that, a young girl finding her calling. After having heart-to-heart conversations with funeral directors around Idaho and Oregon that I interviewed, they suggested I get a job in the field first before committing to mortuary science school (I already had two bachelors degrees at this point and getting a third was something I needed to think about) to see, you know, if I had the stomach and the heart for such a gut-wrenching career.

It was so hard, they said. I wouldn't recommend this field to anyone, they shared. It is a calling and a career that can keep you up all night and away from your family on birthdays, they lectured. Funeral directing will drive you to drink, they warned.

They hired me at one of two funeral homes in Corvallis to be a mortician's assistant/night-time removal driver. I had a pager and worked full time during the day, awaiting deaths in the dark of the night. And they came, sometimes more than one a night. And I took off my pajamas and brushed my teeth and threw on some nice conservative black clothing, drove to the mortuary, picked up the unmarked minivan and met the family/nurse/staff/police at a number of locations. Physically, dead weight is hard to carry. Emotionally, it's even harder.

I have stories to tell that will knock the wind out of you, make your stomach churn, make your heart break. People hugged me, screamed at me, said I was too young, too beautiful, too sweet to be doing this job.

You make me feel better, she said. Your kindness is so soothing, they told me. I'm floored that a young woman is here to take my father away but I'm so glad you are, I once heard. I hate you, she cried. Please don't take him away, they yelled down the hall, tearing at my clothes.

In graduate school I found myself studying art and architectural history, continuing to learn about the American way of death. These stories bore a hole in my heart and my mind and my academic research. It can be different. It should be different.

Caitlin Doughty is a mortician who's telling you that you don't really need a mortician to mourn and bury your loved ones. Home funerals and green burials and bringing death back to our conversations is such an important movement. She's also founder of The Order of The Good Death and writer of a new book and recently interviewed by Terry Gross on NPR. All of these things are so, so, so worthwhile, friends. Please give them a watch, read, glance. It's kind of a matter of life and death.

And fun! (For real.)