I learned as a teen that my body was a political vessel and I often use it as a canvas for my art and activism. Over the years I’ve done several performance art pieces and guerrilla art installations geared around bodies in Boise and they’ve received mixed reviews – from hateful to positive. As a fat feminist body image activist I also use social media as a revolutionary tool in sharing my art and my message of body positivity, which includes talking about a lot of things important to me as a woman, like aging, motherhood, my sexuality and bodies. I believe strongly that you cannot make positive change as a social activist unless you clearly understand where and who has worked before you and your place in history. When not using my writing and body as artistic tools, I will sometimes use printmaking combined with found objects and stitching. My two-dimensional artwork often blurs the boundaries between fine art and craft. For me, the repurposing of found materials adds both tactile and historical elements integral to the contemporary story each piece tells. My foundations with fabric and needlepoint, combined with my academic background, have allowed me to explore traditional women’s handiwork in a non-traditional way as part of a movement called craftivism. As a writer I think a lot about words and they often play a big part in my art. Their history, meanings, double entendres, spellings. How we fling them, mean them, change them, reclaim them.

Slut is one of the words that have been used against women, myself included, for decades. It’s typically meant in a derogatory way, making a judgement on how a woman dresses, how many sexual partners she has had, if she dares to talk about her sexuality in a positive way. As far back as 1380 we see the word used to describe a slovenly or dirty man and by 1450 it was often used to describe women similarly, especially kitchen maids. There is also an old reference to a slut also being a homemade candle of sorts (which is, interestingly, how we see it used in an Idaho Statesman newspaper article about Atlanta, Idaho, in 1873). By the 1800s it is usually a word to refer to a woman of “loose morals,” and our own Idaho Statesman corroborates this and follows the national usage of the term. In the 1950s the word appears a few times in the Statesman, in reference to a female prostitute character in a Broadway play and a Biblical reference to Salome. In the 1960s and 70s the term appears more in our newspaper, often in Dear Ann Landers’ columns about young women who have gotten pregnant out of wedlock and wives cheating on their husbands. There are also numerous concerns about The Man of La Mancha coming to the Morrison Center for Performing Arts and the important character arc of a woman’s “transformation from a slut to an ideal woman.” By the turn of the century slut has absolutely entered our vernacular and it’s used over and over in the newspaper, in regards to things like Monica Lewinsky, the play Avenue Q (again at the Morrison Center), sexting and teens, sexual abuse and harassment. For the past ten years, at least, the reference to slut in the newspaper has been in regards to the damage slut-shaming can to do women – emotionally, professionally and legally.

Mention of a French slut in the fiction piece Moonhollow printed in the Idaho Statesman, August 29, 1942

A mom’s shocking letter to Ann Landers filled with slut shaming and fat shaming of her pregnant daughter, printed in the Idaho Statesman, March 17, 1970

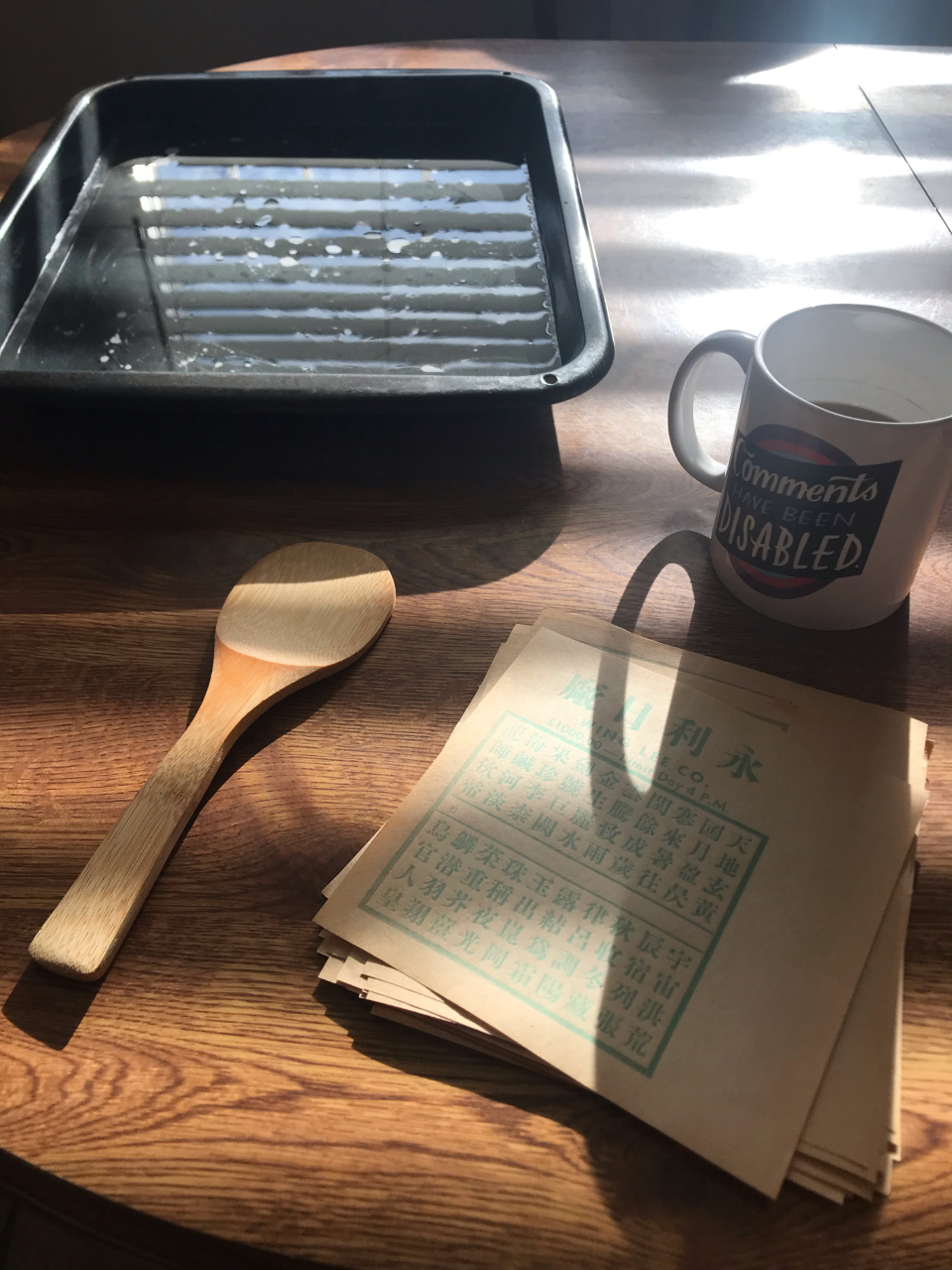

I recently created this piece for Wingtip Press’ annual printmaking exchange and exhibition called Leftovers, as it was created to use the leftover small pieces of paper and odd supplies found in artist studios. I’ve participated for years and my work always come from other “leftovers” in house, particularly otherwise mundane items from history and my life as a woman and mother, like birth control pill packets and paper dolls. This year’s pays homage to the history of this controversial word as well as paying homage to the historical home of institutionalized “sluttery” in Boise. It was called Levy’s Alley, Boise’s largest red light district prior to its demolition in 1909 on the site of today’s City Hall, mixed into the site of Boise’s original Chinatown on the same square block. Both groups, whose bodies, differences and choices, made them marginalized and “othered” (as also noted in many an Idaho Statesman article from the time), were pushed out to neighborhoods a few blocks away. Both the Chinese population in Boise, which, at one time, rivaled the size of Seattle’s and San Francisco’s Chinatowns, and our prostitutes were beloved, necessary, important members of our Western town and at the same time treated poorly and reviled. The vintage keno lottery tickets were something that could be found in most Chinese shops in the early 20th century, and these were saved just before the demolition of the Hop Sing Building downtown Boise in the old Chinatown at 706 ½ Front Street, built in 1924 and demolished in 1972.

The Hop Sing building (b. 1924) downtown Boise was in Chinatown until it was demolished in 1974. It was on 7th Street (renamed Capitol Boulevard) near where the new parking garage is today north of the Grove Hotel. (photo courtesy Idaho State Archives)

Leftovers (Get Lucky), 2019

Medium: image transfer print on plastic stitched to vintage Boise Chinatown keno ticket c. 1960

*The show opens this Friday night May 5, 2019 at Push & Pour in Garden City, Idaho, with a silent auction of prints (including mine!) if you’re interested in purchasing it. I have to tell you, this exhibition is stellar and this year’s prints might be my favorite of all time. You can see more of them here along with show event details.